Phone: 519-736-2511 Email: info@parkhousemuseum.com

The Painter’s Case

The Park House is home to the Amherstburg Community Collection. We have a variety of items from toys, home furnishings, art, militaria and farm equipment to clothing and artisan tools. While our full exhibits tend to focus on one particular theme complimented by multiple objects within the topic, we’ve decided to look at one object and its contents in this display.

Click on any of the images below to see a larger version.

Most of the items in the Park House collection have been donated by members of the community, but this item was purchased in September of 1986 for the sum of $135.00.

It’s a seemingly plain brown leather suitcase with worn dark red corners and a lockable metal latch. The case was still filled with the painter’s equipment for faux wood graining/ faux bois.

Wood Graining/Faux Bois

Wood graining is the art of imitating wood by painting and was part of the trompe l’oeil tradition in the second half of the 19th century. Graining was a way of making doors, walls, furniture, and other objects look fancier than they really were. Pine, for instance, was often painted to resemble more costly woods such as oak or mahogany.

This historical precedent goes back well before the 19th century. Also called ”faux bois” or ”false wood,” wood graining has been practiced for thousands of years. According to ”The Art of the Painted Finish for Furniture and Decoration,” by Isabel O’Neil, wood graining was used in the Bronze Age to decorate pottery. The Egyptians employed it during the third and fourth dynasties, and doors and wainscoting at Fontainebleau were painted as imitation cypress.

The technique of graining is not difficult to learn. Knowledge of the different characteristics of wood – the flow of the grain, the knots and the colors is important, as are the proper tools.

Very simplified, wood graining works like this: The surface to be painted must first be cleaned, sanded, and then sealed. Next, a base coat of paint, the color of which is the lightest tone in the wood being imitated, is applied and allowed to dry. The third step is to apply a graining pigment.

If a more realistic effect is desired, an opaque graining pigment is applied with a graining tool such as a pipe overgrainer or a graining brush. When a more imaginative effect is preferred, a glaze (a transparent film of color) is applied and then wiped off with almost any object, such as sponge, chamois, straw or a thumb.

– THE ART OF PAINTING A SURFACE TO LOOK LIKE WOOD – The New York Times

James Oxley, Sheffield Ltd.

Two spreading knives within the painter’s box were made by James Oxley Sheffield Ltd.

John Oxley was a shoe and butchers’ knife manufacturer, who was listed in Whitecroft in 1822 (a later trade advertisement gave an establishment date of 1797). By 1825, he was based in Hollis Croft. John apparently died in about 1837. He had two sons – George (1808-1879) and James (1811-1881).

The brothers took over their father’s firm, first in Hollis Croft and then by the 1850s at No. 56 Garden Street. In 1855, they exhibited at the Paris Universal Exhibition. In 1861, George told the Census that he employed a dozen men and six boys. However, in that year, the partnership was dissolved. George died on 5 September 1879, aged 71. His brother continued the firm.

By 1868, James was listed as a maker of cooks’ and palette knives and steels in Garden Street, with a ‘depot for inventions of domestic utility’ in Devonshire Street. One of his ideas was a patent bread slicer. In 1871, he employed five men and a boy and a girl. He died on 2 June 1881. The firm – now employing ten men – was under James’s son, James Jenkinson Oxley (1844-1911). Until the 1880s, the firm regularly advertised in the Sheffield trade directories. Oxley’s trademark was a butcher’s knife crossed with a sharpening steel (and the letters ‘JO’).

Before the First World War, Oxley’s Garden Street factory was known as Toronto Works. James J. Oxley died on 6 February 1911. His sons – Ernest James Oxley and William Bernard Oxley – kept the firm in family hands. It was an enduring presence at 36 Garden Street – selling painters’ cutlery and tradesman’s tools – until the 1960s. The last family partners were William Bernard Oxley and his son, John Edwin. In 1969, George Barnsley & Sons acquired Oxley’s and made a limited company. Its final address was Cornish Works, Cornish Street until it was dissolved in 2005.

– James Oxley (Sheffield) Ltd.

Boydell Brothers White Lead and Color Company

This box of paint colour samples was in the painter’s box in our collection; it was samples of the paint sold at Boydell Brothers White Lead and Color Company. The sons of John Boydell ran the company. John began the company in 1865, but it was his son’s marketing and business sense that made it most successful. Originally from England, immigrated to London, Ontario briefly before finally settling in Detroit, Michigan. The firm was in operation until 1959. The family’s home still stands in Detroit.

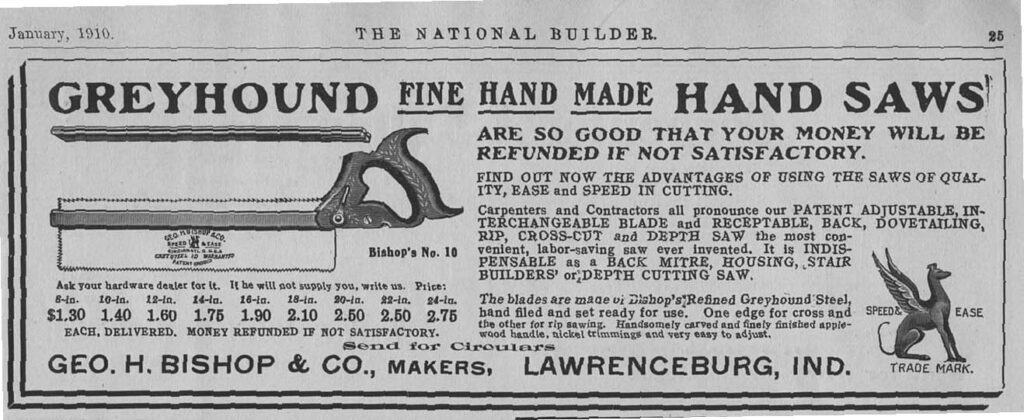

Geo. H. Bishops & Co.

Looking closely at the steel combs. There is a square metal piece with the logo for Geo. H. Bishops & Co. After doing some investigating, we discovered it was a repurposed Greyhound Saw. The artist had cut down the saw to repurpose its use as a modified steel comb. Clearly they admired the logo as well.

Standard Varnish Works

Standard Varnish Works company was out of Staten Island, NY. It opened in the 19th century, and they purchased their office building in 1892 – 93. By the 20th century, they established themselves as the largest varnish and enamel manufacturers in the world. By the time the Toctch Bros bought out the company in 1926, they had operations in New York, Chicago, Toronto, London, Paris, Berlin, Milan, Barcelona, and New Jersey. After changing hands numerous times, the current company still exists under the name Standard T Chemicals and still employs between 11 and 50 people. The original office building still stands in New York today and is awaiting a heritage designation.

Artist/Painter’s Sketches

Unfortunately, we do not know who the original owner of the box was, but they did leave behind some sketches. We inverted the colour on the sketches for better view of the details.

We would like to thank the Ontario Trillium Foundation for making the digitization of our collection possible. We would also like to thank our donors (past, present, and future) for entrusting our museum with the preservation of their donated objects. Finally, thank you to our intern Jordan and Carly for their work assisting with the content of this exhibit.